Servicemen are key to military success, so a book about future war must include manpower issues. This is a vast topic, yet there are areas where a military can make major improvements by tweaking their manpower system. Some think more pay and benefits create a better force, however, a military is allotted only so much funding. A moderately paid force of two million soldiers is more powerful than a highly paid force of one million. Most people are surprised to learn the US military spends more money on personnel benefits than on basic pay once veterans and retirement costs are included. These ideas are directed at the US military, but can be adopted by any military.

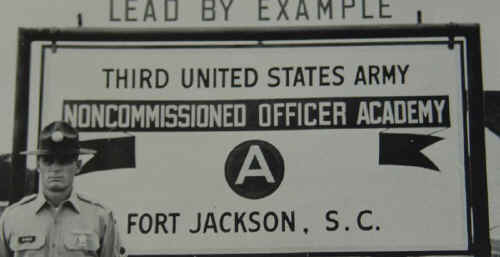

A Professional NCO Corps

The US military has not adjusted to an all-volunteer military. Prior to World War II, enlisted men served a decade before they became an NCO (or PO "Petty Officer" in the Navy and Coast Guard). The rapid expansion of the U.S. military during World War II and high turnover due to later peacetime conscription sped up promotions and becoming an NCO in two years was not uncommon. Everyone who avoided serious trouble was rapidly promoted to the NCO ranks to encourage reenlistments. This problem persists today, so young NCOs often act, and are treated like "troops."

Much higher pay has greatly improved recruit quality and retention. The US Army

refuses to enlist 75% of Americans who apply and says

one out of five Nevada high school graduates who inquire are not smart enough to

join. The US military has not used this advantage to develop more experienced

and properly trained NCOs. GIs do not attend an NCO school prior to becoming

one, and since most troops leave after their four-year enlistment it's a waste

of resources to send all E-3s to an NCO school.

Much higher pay has greatly improved recruit quality and retention. The US Army

refuses to enlist 75% of Americans who apply and says

one out of five Nevada high school graduates who inquire are not smart enough to

join. The US military has not used this advantage to develop more experienced

and properly trained NCOs. GIs do not attend an NCO school prior to becoming

one, and since most troops leave after their four-year enlistment it's a waste

of resources to send all E-3s to an NCO school.

While some newly commissioned officers face criticism as "90-day wonders" for just competing Officer Candidate School (OCS), becoming an NCO is mostly automatic with no requirement to complete any NCO training. An important step toward a truly professional NCO corps is to stretch out promotions for junior enlisted so that four years of service is required, along with completion of a serious NCO school.

The first problem is that junior enlisted are promoted too fast. Two promotions during the first year in service is mindless! Normal promotion to E-2 should be after one satisfactory year in service, which is double what is required today. Normal promotion to E-3 should be after two satisfactory years in service. Each military service controls their enlisted promotion process but these timelines are common.

Typical Promotion to:

E-2 - now 6 months in service, but should be 12 months.

E-3 - now 10-12 months in service, but should be 24 months.

E-4 - now 24-36 months in service, but should occur as GIs graduate from NCO school after 48 months.

Stretching out promotions to a reasonable pace would allow the selection process for E-4 to merge with the reenlistment process. Promotion to E-4, the first NCO grade, should occur after four years in service. E-3s accepted for reenlistment must also complete a formal NCO school. This would not be a quick 2-4 week local program but a serious 10-week national program similar to OCS. If accepted for reenlistment an E-3 would get TAD/TDY orders to an NCO school at the end of their first enlistment, often en route to their next duty station.

This would not be a fun school where 100% graduate. They would live in open

barracks and return to a basic training environment with drill, physical

fitness, hiking, and weapons training, during a six-day a week/14-hour a day

training schedule. Around 95% would graduate since they were recommended by

their command. Some will not because they arrived obese or unable to pass a

basic physical fitness test, despite assurances from their slack sponsoring

command. Others developed an ego or became lazy during their enlistment and feel

too important to engage in tough training. Some highly trained GIs have six-year

initial enlistments. Most would be sent to NCO school at their four year mark,

and the few who fail would finish their last two years as an E-3. Upon

graduation, all would be promoted to E-4 and welcomed into the NCO ranks during

a formal ceremony.

Promotion to E-4 in the reserves and National Guard would require completion of the same 10-week active-duty NCO school. Capable E-3s with four years of service in the reserves would be offered a chance to attend NCO school for promotion to E-4. If they are too busy in civilian life to attend, they are too busy to become an NCO. They would attend alongside regular soldiers, which would greatly enhance professionalism and cooperation in the Total Force. In addition, many outstanding E-3s in the regular force are not interested in reenlisting, but would express interest in NCO school and promotion to E-4 if they enlist in a local reserve or National Guard unit. NCO school would prove an attractive recruiting tool for the reserves as a highly paid "summer job" for veterans attending college.

NCO Chevrons

The armed services must clean up their chevron mess. An E-1 with no chevrons looks just like a young officer from the side. (pictured) Recruits should get a stripe at graduation from basic training. This would be a simple hash mark for the Navy and Coast Guard, whose titles and insignia clearly separate young NCOs (POs) from seamen.

The Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps need to simplify their chevron mess since

they often operate jointly. It's so bad that few Generals can identify the grade

of enlisted from all the armed services. This problem is never addressed when

the need for "jointness" or greater NCO respect is emphasized. Most

GIs cannot look at the chevrons of other services (below) and distinguish troops

from NCOs. A Marine Corps Private First Class is an E-2, but is an E-3 in the

Army. Some titles are confusing, like the odd Marine Corps E-3 title of

Lance Corporal. The Army's strange E-4 "Specialist" title is an

outdated rapid promotion idea from decades ago when pay was low and recruiting

difficult.

The Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps need to simplify their chevron mess since

they often operate jointly. It's so bad that few Generals can identify the grade

of enlisted from all the armed services. This problem is never addressed when

the need for "jointness" or greater NCO respect is emphasized. Most

GIs cannot look at the chevrons of other services (below) and distinguish troops

from NCOs. A Marine Corps Private First Class is an E-2, but is an E-3 in the

Army. Some titles are confusing, like the odd Marine Corps E-3 title of

Lance Corporal. The Army's strange E-4 "Specialist" title is an

outdated rapid promotion idea from decades ago when pay was low and recruiting

difficult.

Civilian leaders must demand standardization. In the Army, Air Force, and

Marines an E-1 should be a Private Third Class with one stripe; an E-2

Private Second Class with two stripes; and an E-3 Private First Class with three

stripes. All would be addressed as "Private." These may be straight

hash marks like the Navy or V stripes used by the British, the US Army prior to

1902, and the US Air Force today. As a result, Private Jones would be called

"Private Jones" as an E-1, E-2, and E-3, in the Army, Marines, or Air

Force, so the jump to an E-4 corporal would be dramatic. Titles for E-4s

should be altered to clarify their leadership status, like our Navy and Coast

Guard. For example, an E-4 Air Force Corporal is better than "Senior

Airman" and the Air Force should invert their chevrons for E-4s and above

to match the Army and Marine Corps.

Civilian leaders must demand standardization. In the Army, Air Force, and

Marines an E-1 should be a Private Third Class with one stripe; an E-2

Private Second Class with two stripes; and an E-3 Private First Class with three

stripes. All would be addressed as "Private." These may be straight

hash marks like the Navy or V stripes used by the British, the US Army prior to

1902, and the US Air Force today. As a result, Private Jones would be called

"Private Jones" as an E-1, E-2, and E-3, in the Army, Marines, or Air

Force, so the jump to an E-4 corporal would be dramatic. Titles for E-4s

should be altered to clarify their leadership status, like our Navy and Coast

Guard. For example, an E-4 Air Force Corporal is better than "Senior

Airman" and the Air Force should invert their chevrons for E-4s and above

to match the Army and Marine Corps.

Sending all E-3s selected for reenlistment to a formal NCO school would not cost more money if promotion timing is slowed, since lower-ranking GIs are paid less. Moreover, our military would no longer waste money sending junior GIs to varied short leadership schools unless they've signed papers to reenlist in the active force or reserves. NCO school should become as necessary for promotion to E-4 as OCS is for a second lieutenant. These simple changes would quickly improve the quality and morale of the enlisted force. All "troops" (E-1/E-2/E-3) should be called private or seaman, and all NCOs should have clear leadership chevrons and titles. Everyone would respect a young corporal knowing that he has more than four years in service and graduated from a serious NCO school.

Deployment and Combat Pay

Fair compensation is a major problem. The administrative system wants to pay all those of the same grade and time in service the same pay. However, deployed servicemen work twice as much of those back home, while those in combat suffer and risk their lives. What really upsets soldiers in combat zones are comrades who pulled strings, got pregnant, or faked injuries to avoid a deployment and combat duty, yet receive nearly the same pay and benefits. The US military pays $225 a month hostile fire allowance to those in combat zones, but that doesn't fully compensate them. There is a combat zone tax exclusion, but that causes tremendous confusion and administrative burdens.

To correct this inequity, deployed servicemen should be paid an additional 50% of their basic pay. Any servicemen deployed away from his home base for 16 consecutive days during a calendar month is paid 50% extra. This money will be paid from unit operational or theater command exercise accounts, not from personnel accounts. As a result, commanders will pay attention to how long servicemen are dispatched for temporary duties or field exercises as they must be paid 50% more, and that money will come from "their" funds. If a General wants to dispatch an aircraft squadron overseas for a few months, he must find funds to pay those servicemen 50% more for the extra work he expects them to perform. If no command wants to fund his idea, then it must not be important. This means major month-long training rotations to places like Fort Irwin will require extra pay for the servicemen involved, and they deserve it.

If a servicemen is in a combat zone for

16

consecutive days

during a calendar month, he should also be paid 50% more in compensation. Therefore, servicemen in combat will be paid 100% more than those back home

since they are deployed as well. Theoretical exceptions are possible, like

if a non-deployed soldier in Korea is fighting to defend his base, he just gets

the extra 50% for combat pay. This 16-day requirement eliminates abuse of

the current combat pay rule that only requires one night in a combat zone to

earn combat pay for that month.

Navy ships have been known to divert course to enter certain waters for a night

so all aboard can collect undeserved "combat pay." Senior

officers who visit a combat zone and stay a night also get "combat

pay" for that month.

If a servicemen is in a combat zone for

16

consecutive days

during a calendar month, he should also be paid 50% more in compensation. Therefore, servicemen in combat will be paid 100% more than those back home

since they are deployed as well. Theoretical exceptions are possible, like

if a non-deployed soldier in Korea is fighting to defend his base, he just gets

the extra 50% for combat pay. This 16-day requirement eliminates abuse of

the current combat pay rule that only requires one night in a combat zone to

earn combat pay for that month.

Navy ships have been known to divert course to enter certain waters for a night

so all aboard can collect undeserved "combat pay." Senior

officers who visit a combat zone and stay a night also get "combat

pay" for that month.

However, defining a combat zone is complex. This has been abused by Generals in recent years who designated entire nations like Egypt and Saudi Arabia "imminent danger" areas because of a terror threat. As a result, servicemen in these comfortable rear areas received $225 extra a month, which infuriated those shot at on a daily basis. A better definition is a flexible one. If a servicemen is killed by enemy action, all servicemen within 100 miles are eligible for combat pay that month. This is simple to determine in a real war where several servicemen are killed every week so everyone near the fighting earns combat pay each month, except those in the deep rear areas. However, those in deep rear areas like Saudi Arabia may collect it occasionally due to a terror bombing or missile attack. Of course this will lead to some perverse thoughts when fighting has slowed and the end of the month is near, but no one has been killed within 100 miles of a camp. That's good no one has been killed, but...

Servicemen love the idea of substantial deployment and combat pay, but experts will state there are no funds for these extra pays. There are funds, in the current personnel budget. Annual pay raises can halt for a couple of years to shift funding to pay deployed soldiers and those in combat more since they work the most. Critics will call this a pay cut, but the personnel accounts will not be cut. Pay will be rebalanced to reward those who are working two or three times more hours each week than those back home. This may upset those who never deploy, yet please those who do, which are the ones an army wants to retain in uniform anyway. This compensation adjustment will greatly improve morale as servicemen who deploy and must fight overseas are paid twice as much, and are less angered by those who stayed home. This is a real way to "support the troops" fighting wars.

Unpaid Leave

Many servicemen leave the US military because they are burned out or want to spend more time with their family. One solution is to allow from 3-12 months of unpaid leave between permanent change of assignments, or on rare occasions, with permission from a Commanding General. At least three months must be taken due to the administration involved in stopping and starting pay. Retirement and leave credits will not be earned, but medical benefits will remain in place. If unpaid leave is taken during a permanent change of station move, servicemen can pay movers to store household goods for a few months to save money on rent.

Some servicemen will take unpaid leave to spend more time

with their children and to visit hometowns. Others will travel the world, or

spend time with a gravely ill or seriously injured family member.

Some need a few months to court and marry their darling back home. Many

can finally finish a college degree by taking unpaid leave to attend college full-time for one or

two semesters. Finally, some servicemen are stressed out after a decade of service

and just want to fish and watch television for a few months.

Some servicemen will take unpaid leave to spend more time

with their children and to visit hometowns. Others will travel the world, or

spend time with a gravely ill or seriously injured family member.

Some need a few months to court and marry their darling back home. Many

can finally finish a college degree by taking unpaid leave to attend college full-time for one or

two semesters. Finally, some servicemen are stressed out after a decade of service

and just want to fish and watch television for a few months.

This can save many marriages strained by one-year deployments. Servicemen can promise to take six months off when they return, which is affordable if they earned 50% more from deployment pay. Others have wives who demand that a career servicemen retire after 20 years. She may compromise and agree to 24 years if he proposes taking an entire year off near the 18 year mark. Of course money is an issue, but servicemen are much better paid nowadays, and everyone knows how to use credit cards when they need to. Many servicemen decline large reenlistment bonuses because they really need time off. However, a bonus combined with unpaid leave can retain many expensively trained servicemen. A serviceman returning after months of unpaid leave will be refreshed and eager to work and earn money once again. An unpaid leave option will increase retention and improve morale, yet cost the US military nothing, except some minor administrative headaches.

Enlistment Completion Bonus

One problem with a volunteer military is that many soldiers "unvolunteer." After spending considerable money to recruit and train servicemen, many decide they do not like the military or their assignment or their boss. Some use illegal drugs or become disciplinary problems and are discharged. Others become overweight or lazy. Many desert and chasing them down for prosecution is expensive and somewhat pointless. In the US military, some 30% of first-term enlistees fail to complete their enlistment. This is very expensive and hurts readiness.

The basic problem is there is no reward for completing an enlistment. All militaries should pay a bonus to those who complete the terms of their first enlistment contract. Funding is an issue, but one solution is to deduct 10% of basic pay from first-term enlistees for their "completion bonus." Recruiters need not mention this unless asked; it is money that will be paid to soldiers eventually, if they complete their enlistment. In the US military, this will amount to around $200 a month, or $2400 a year withheld. That will total a nice $9600 after a four-year enlistment.

This will provide an incentive for servicemen to complete their enlistment, improving discipline and morale because drop-outs forfeit their completion bonus. This can save the US military a few billion dollars a year as thousands more finish their enlistment, reducing the need to recruit and train replacements. In addition, the military keeps the 10% withheld from those who fail to complete their enlistment. Those discharged for good reason like a serious injury will receive whatever completion pay has accumulated. If a servicemen leaving is eligible for an honorable discharge, he will receive completion pay, those pushed out with general or dishonorable discharges will not. Servicemen who reenlist will receive their completion pay earlier, as soon as they reenlist. This forced savings plan will help those who accumulate debts during their youth, and provides money for those who wish to take a few months of unpaid leave.

Officer Intelligence Testing

The officer promotion process is one of the weakest elements in the US military. Performance rating systems have become inflated to the point they are useless except for serious punishment. As a result, many officers lacking intellect manage to accumulate an excellent record for promotion. They use flattery while avoiding problems and rely on subordinates to get their job done. Their superiors mark them outstanding as is customary although those who work with them know they are incompetent. They may be polite and hardworking, but have difficulty understanding new concepts or even basic math. Nevertheless, so long as they stay out of legal trouble, don't rock the boat, and demonstrate total loyalty to their boss, they are often promoted into the career force. All career military men can recall a few Colonels and even Generals who were of below average intelligence, yet through good looks and charm, family connections, or winning a high award for heroism, they moved to the top.

One solution is to require all officers to take the Graduate Management Admissions Test (GMAT) within two years before consideration by a promotion board for O-3, O-4, O-5, and O-6. Officers who fail to take the test would be passed over for promotion. The GMAT is a key part of the selection process for all graduate business schools. It is much better than the simple vocabulary/math test used for SAT and ACT college entrance examinations. The GMAT involves reading comprehension, deductive reasoning, and problem solving. Universities use testing because of the difficulty in comparing grades and accomplishments from hundreds of undergraduate schools with varied standards and different levels of peer competition. Likewise, the GMAT can help military promotion boards at no cost to our military. Officers can take the GMAT at any of the hundreds of test sites around the globe and simply enter a code on their test form so their official score is sent directly their to their service record branch.

Intelligent officers are often frustrated by military service since everyone is

generally promoted at the same pace, based solely upon pleasing their raters and

working the bureaucracy to secure the best career path. They may irritate

superiors by trying to fix problems others don't recognize. The brightest

lieutenants soon realize they will advance at the same rate as below average

officers. There is no easy solution to this problem, but if GMAT scores were

part of the promotion process, they would be encouraged to stay in the military

knowing they have an edge.

Intelligent officers are often frustrated by military service since everyone is

generally promoted at the same pace, based solely upon pleasing their raters and

working the bureaucracy to secure the best career path. They may irritate

superiors by trying to fix problems others don't recognize. The brightest

lieutenants soon realize they will advance at the same rate as below average

officers. There is no easy solution to this problem, but if GMAT scores were

part of the promotion process, they would be encouraged to stay in the military

knowing they have an edge.

If GMAT tests are required, officers will devote thousands of hours to improve their GMAT score. They will work on math puzzles, read more books, and study vocabulary. These years of self-study for the GMAT will improve the mental agility of all officers. This is far better than the current incentive to please their raters by improving their golf game or hosting dinner parties. A GMAT score will also help select the best candidates for military funded graduate-level schools.

Former President George Bush was admitted to Yale only because of family connections; his grandfather lived next door to the Dean. This family tradition ended when Yale began to require SAT scores as part of the admission process, so George's younger brother Jeb went to the University of Texas. Standardized testing is not the solution for selecting officers for promotion, but requiring the GMAT will inject an element of fairness and provide a valuable tool to improve the quality of the officer corps.

End Early, Early Retirement

Most militaries have a retirement system, which becomes more costly every year as people live longer and the cost of new health care technology and drugs needed to keep the elderly alive rises rapidly. In 1950, American life expectancy was 68.2 years, which rose to 78.7 by 2010. This trend indicates that people joining the US military today at age 18 and retire at age 38 may receive retirement pay and full medical benefits for another 44 years until they die at 82 years of age. As a result, these servicemen will collect retired pay for TWICE as long as active duty pay.

This has caused personnel costs to soar. The US military now spends more on a force of 1.3 million active duty personnel than it did on 2.1 million personnel in 1983, even after adjusting for inflation. Most of this cost is the result of two decades of annual pay raises above the rate of inflation. These pay raises also increased eventual retirement costs, while retirees live longer each year. Prior to World War II, servicemen had to serve until age 60 to retire and collect a monthly retirement check. Back then, the US military paid the average retiree benefits for only around seven years since life expectancy was 67 years. Returning to that standard is possible, but will upset those who expect retirement checks in their middle-age.

It has become normal in the confused world of the US military for someone to "retire" and then take a job on a military base and earn another paycheck from the military, or through a contractor. This is very lucrative, but "double dipping" is expensive and counterproductive since it encourages highly trained people to "retire" in their 40s. For example, during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the US military had manning problems as many senior enlisted men retired so they could earn more money as security contractors funded by US military contracts.

If the US military is to survive in a future where most people live past age 100, Generals must propose changes now so that new enlistees cannot collect a retirement check until age 50. After 20 years of service they can transfer to a reserve status and pursue other careers, but they will not receive monthly retirement checks until age 50. They will retain medical benefits and access to base facilities. This is similar to the retirement system for reservists, who can "retire" after 20 years, but do not receive a monthly check until age 60.

This will allow those who join at age 30 to receive a retirement check immediately after 20 years of service at age 50. This may seem unfair, but this is the identical benefit for someone who served 20 years on active duty from age 18 to age 38. Assuming both live until age 82, they will both receive 32 years of retirement pay starting at age 50. As part of this change, enlisted careers should be stretched and senior enlisted E-7 and above allowed to serve until age 50 if they remain fit, rather forcing them to retire in the 40s because of arbitrary time-in-service limits.

The advantages of this plan are immense, far beyond the money saved in retirement costs. First, highly skilled servicemen are less likely to retire when they become eligible after 20 years of service, thus improving military readiness. Second, those who shift to a reserve status after 20 years of service can join a reserve unit and draw reserve pay until age 50. This will greatly enhance cooperation between active and reserve components since many of senior reservists will have more than 20 years of active experience, and will improve the quality and skills of reserve units. For example, an experienced pilot costs millions of dollars to train yet many retire after 20 years, or may be forced to retire after failing promotion around age 44. These experienced pilots would love to fly in the reserves until age 50 to fill vacancies, but they cannot join a reserve squadron today because they receive retirement checks.

Reserve duty will pay $800 a month to an E-7 with 20 years of experience. In addition, they can earn credit for each day on duty toward their retirement pay calculation at age 50. Therefore, an E-7 who transfers to the reserves at age 38 after 20 years of active service may spend 12 years in the reserves, so his retirement pay will be based on ~21 years of total active service. If his unit is mobilized, it will be more than that. Another advantage is that many servicemen who retire early have a desire to return to the active force after a few years in the civilian world. However, it seems wasteful to give up retirement pay, and the bureaucracy discourages this. If he were not receiving retirement pay, he is much more likely to reenlist in the active force to fill a vacancy. Reserve duty isn't required and many will prefer to remain in the inactive reserve until their retirement pay kicks in at age 50.

Longer careers will mean that retirees earn a larger monthly check, but they will do so for fewer years. Moreover, the military will get more mileage out of each GI so fewer career servicemen are required and fewer retirees produced. For example, the armed services shape their manpower so around 100,000 enter the career force each year, e.g. those who will serve until they retire after around 24 years of service. If they were encouraged to serve an average of 28 years by delaying retirement pay to age 50, only around 85,000 are needed to enter the career force each year, eventually resulting in 15,000 fewer retirees each year. Given that retirees live another 40 years, that would eventually reduce the overall number of retirees by some 600,000!

The only objection is that this may hurt recruiting and retention. However, collecting a retirement check at age 50 is very attractive and much younger than retirement plans elsewhere in the nation. Some 40% of Americans who pay taxes to fund military retirement have no pension other than Social Security, where the retirement age is gradually increasing from to 68. The only opposition may be from military groups who oppose any reductions for any reason. However, they should understand that it was easy to provide generous retirement benefits after World War II because little funding was required since pay was low and it would be decades before the large numbers of servicemen from World War II and the Cold war retired.

At one time the US military was known for low pay but great retirement. Military pay has surged these past two decades so that servicemen now make around 90% more than Americans with similar skills, a figure that does not include the value of their generous retirement plan. In addition, military retirees are living ten years longer than after World War II and life expectancy will continue to grow. The retirement pay burden is a growing threat to America's national security, especially with large budget deficits. Something must be done now for the good of the nation and the armed services. Projections show that at current spending levels, overall personnel costs will grow to devour the entire Pentagon budget by 2030! If current service members want to ensure full funding for their retirement, they should support a law that delays retirement pay for new enlistees until they reach age 50.

Manpower Challenges

Manpower is very costly for a modern military so funds must be properly allocated. Generals should suggest alternatives to reduce manpower costs other than simply shedding manpower. The best idea was Marine Corps General Mundy's effort from two decades ago to bar junior Marines from marriage. That failed for political reasons, but the same objective could be reached with a return to the old policy of limiting family housing benefits to E-4s and above. This should be combined with stretching out promotion to E-2, E-3, and E-4 to develop Professional NCOs. These steps would save enough to maintain at least 50,000 more on active duty.

Making changes is difficult because most people are greedy and do not care what is fair and best for their nation. As a result, politicians fear change, especially when good ideas are attacked by unions and organizations that distort the truth. While military officers consider themselves fearless, it will take brave souls to correct costly and counterproductive pay schemes. Unless action is taken soon, personnel costs will swallow all US military funding now used for procurement, leaving a hollow military with ageing equipment.

©2015 www.G2mil.com