____________________________________

Despite a massive budget, the US military

has no serious amphibious landing capability against a defended coast. This

is because American naval officers are unfamiliar with amphibious

invasions and procure ships unsuited for this mission. Marine

Corps officers only plan for small amphibious seizures, which are much

different. Some ramble nonsense about tiny MEUs with just 2000 Marines (and

only 600 are ground combatants) conducting "forcible entry" amphibious operations. Army

officers seem unaware that the US Army conducted massive amphibious

operations during World War II and ramble nonsense

about airborne operations.

Despite a massive budget, the US military

has no serious amphibious landing capability against a defended coast. This

is because American naval officers are unfamiliar with amphibious

invasions and procure ships unsuited for this mission. Marine

Corps officers only plan for small amphibious seizures, which are much

different. Some ramble nonsense about tiny MEUs with just 2000 Marines (and

only 600 are ground combatants) conducting "forcible entry" amphibious operations. Army

officers seem unaware that the US Army conducted massive amphibious

operations during World War II and ramble nonsense

about airborne operations.

The US Navy has 33 huge, expensive, vulnerable, and inefficient "amphibious" ships that cannot safely operate within a hundred miles of an enemy coast. Most of their design is wasted with well decks filled with landing craft and hangar decks filled with helicopters and tiltrotors to act as "connectors" to shuttle men and material ashore. (An LCAC inside an LHA is pictured.) These expensive, vulnerable, and unarmed connectors add no combat power and cannot safely operate within ten miles of an enemy coast because they are easily destroyed by precision guided guns and missiles. The US military has completely ignored the appearance of revolutionary video-guided missiles while lesser powers like South Korea field a deadly multi-role video-guided fiber optic missile. These problems exist because the US Navy's amphibious fleet is no longer amphibious, but devolved into huge, comfortable cruise ships designed to operate in safe seas for extended Third World police missions.

OMFTS is Flawed

Since the US Navy is concerned about shore-based threats, the US Marine Corps accepted a concept of offloading ships from "over-the-horizon," which is about 25 miles offshore. Yet because of the proliferation of long-range self-guided anti-ship missiles, the safe standoff distance to unload is now said to be up to 100 miles offshore! This Operational Maneuver From The Sea (OMFTS) concept launches forces far offshore so that amphibious ships are not required to land forces ashore. Landing small, light, dispersed forces is effective for counterinsurgency operations against a lightly armed enemy with no anti-aircraft, anti-ship, or anti-tank/helicopter weaponry, but OMFTS is impractical for an amphibious invasion for several reasons.

First,

Marines ashore will lack naval gunfire support as the Navy's 5-inch (127mm) guns lack the range to fire more

than 13 miles. Plans to use $200,000 GPS-guided "ERGM/LRLAP" gun-fired

missiles with just a 24 lb. warhead fired from 100 miles away remains an

impossible fantasy. In addition, unarmed minesweepers are

vulnerable if they try to clear lanes near shore without destroyer escort and no

one has explained why large helicopters and unarmored aluminum skinned LCACs (pictured) will not be

destroyed trying to

shuttle material ashore from ships safely at sea. LCACs cost $60 million

each and were sold with the

odd idea that they can land where ships cannot. But what is the point of

securing a shallow spot along a coast that transport ships with an invasion force cannot approach? Another ignored problem is

moving fuel, which accounts for more than half the

cargo needed ashore, but is not easily transported by connectors.

First,

Marines ashore will lack naval gunfire support as the Navy's 5-inch (127mm) guns lack the range to fire more

than 13 miles. Plans to use $200,000 GPS-guided "ERGM/LRLAP" gun-fired

missiles with just a 24 lb. warhead fired from 100 miles away remains an

impossible fantasy. In addition, unarmed minesweepers are

vulnerable if they try to clear lanes near shore without destroyer escort and no

one has explained why large helicopters and unarmored aluminum skinned LCACs (pictured) will not be

destroyed trying to

shuttle material ashore from ships safely at sea. LCACs cost $60 million

each and were sold with the

odd idea that they can land where ships cannot. But what is the point of

securing a shallow spot along a coast that transport ships with an invasion force cannot approach? Another ignored problem is

moving fuel, which accounts for more than half the

cargo needed ashore, but is not easily transported by connectors.

Several studies have proven over-the-horizon invasions impractical, including one from the Naval War College: "Logistical Implications of Operational Maneuver From the Sea," which concludes: "...the Navy and the Marine Corps need to keep the laws of logistics in mind if they are to distinguish campaign plans from fanciful wishes." This and related studies mathematically proved OMFTS impossible to sustain, and these were done assuming offloading 25 miles offshore with no enemy interference! Advocates of OMFTS need classes on the basic math of logistics where one compares how much cargo connectors can move ashore each day to what is required by combat forces. In addition, there are no practical plans to resupply "seabased" ships offshore as their stores are quickly depleted. To get a picture of concerns about OMFTS, look at:

1. Joint Pub 3-02

2. FM 4-95 logistics operations

3. MCWP 4-11 Tactical-Level Logistics

4. MCWP 4-11.6 Petroleum and Water Logistics Operations

5. “Ship to Shore Logistics and the Need for Change” by the UK Defense blog:

Think Defense

6. “Breaking the Tether of Fuel” Military Review Jan-Feb 2007

7. The National Academies of Sciences Study: “Naval Expeditionary Logistics

Enabling Operational Maneuver from the Sea”

The objective of an amphibious invasion is to suddenly seize a port or beach so large follow-on forces can quickly disembark before the enemy can react to the surprise. In 1944, LSTs (pictured) stormed ashore at Normandy to unload 100,000 soldiers and their equipment before German armored divisions could mount a counterattack. At Inchon in 1950, LSTs landed Marines to open the port and allow the US Army's X Corps to quickly disembark and advance inland and capture Seoul before the North Koreans could pull back from the south. OMFTS is for small raids and lacks the firepower for serious fighting. Moreover, Marines will suffer heavy casualties as their vulnerable helicopters, tiltrotors, and LCACs are rapidly shot up by modern defense weaponry.

An amphibious invasion requires landing a powerful ground force before an enemy can counterattack. Attempting to shuttle cargo from ships 100 miles offshore takes ten times longer even with fast LCACs and tiltrotors. In addition, well-deck operations are difficult in mildly rough seas and LCACs can't hover well in white-cap waves. However, ships that move into a protected bay have less problems with difficult seas and offloading ten times faster allows them to depart the dangerous combat area much sooner. Moreover, there are never enough ships to embark the entire invasion force along with needed supplies. Amphibious and cargo ships must offload quickly and return to regional staging areas to embark more troops, equipment, and supplies.

Aerial Assault Madness

Advocates of OMFTS seem unaware of Surface-to-Air-Missiles (SAMs) and Anti-Aircraft Artillery (AAA) because their aerial assault ideas are mad! Operation Lam Son 719 began in early 1971 and was the last major employment of helicopters by the US military. It was launched into Laos to sever the Ho Chi Minh Trail supply line. The United States provided logistical, aerial, and artillery support to the operation. American ground forces were prohibited by Congress from entering Laotian territory, but supported the offensive by rebuilding the airfield at Khe Sanh.

South Vietnam provided its best units for this month long offensive and the Pentagon was confident that American firepower and air mobility would guarantee victory. After a series of bloody battles, the South Vietnamese retreated back home after losing nearly 1600 men. US Army support elements lost 215 men killed, 1149 wounded, 38 missing, and lost 108 helicopters while 7 American fighter-bombers were shot down. All of these aircraft were downed with machine guns and basic AAA weapons as the North Vietnamese had no SAMs in Laos, nor any radar-guided AAA guns, suicide micro drones, or video guided missiles!

During the 1991 Gulf War and 2003 invasion of Iraq, proposals

for major airborne and helicopter assault operations into hostile territory were

considered, but Generals wisely dismissed them. In 1991, the Marines launched a

limited aerial assault called "Task

Force X-Ray" to land an infantry battalion using 51 helicopters

into a blocking position in Kuwait. Despite total air superiority, nearby modern

airfields, and weeks of planning, it was aborted after the helicopters were

airborne. It became evident the operation was too complex and too dangerous even

against a demoralized enemy. In 2003, Army Generals okayed dropping 954 paratroopers in northern

Iraq where American Special Operations soldiers and their Kurdish troops had

already secured the drop zone. It took 15 hours to assemble the scattered

paratroopers in this unnecessary sideshow.

During the 1991 Gulf War and 2003 invasion of Iraq, proposals

for major airborne and helicopter assault operations into hostile territory were

considered, but Generals wisely dismissed them. In 1991, the Marines launched a

limited aerial assault called "Task

Force X-Ray" to land an infantry battalion using 51 helicopters

into a blocking position in Kuwait. Despite total air superiority, nearby modern

airfields, and weeks of planning, it was aborted after the helicopters were

airborne. It became evident the operation was too complex and too dangerous even

against a demoralized enemy. In 2003, Army Generals okayed dropping 954 paratroopers in northern

Iraq where American Special Operations soldiers and their Kurdish troops had

already secured the drop zone. It took 15 hours to assemble the scattered

paratroopers in this unnecessary sideshow.

Helicopters and tiltrotors provide no combat value in serious amphibious invasions. They are great for moving personnel and supplies among ships and staging bases. They are great for sea rescues. Once the coastal area is secured, they are great for moving personnel to the beach and evacuating wounded from safe areas. However, it is foolish to send them near enemy forces. Debates arise about the best aircraft to escort V-22s in combat zones. This is nuts because V-22s, CH-47s, CH-53s, C-130s, and C-17s should never fly over combat zones! Three CV-22s attempted to land in South Sudan in December 2013 and were met with a barrage of small arms fire from loitering, illiterate tribesmen. They were hit 119 times resulting in serious casualties as the CV-22s limped to another airfield. Armed escorts cannot respond until enemy fire downs several aircraft, then the escorts are likely to be shot down too!

Most Air Force Generals think the A-10 its too vulnerable zooming low at 300 knots with a pilot in an armored cockpit. What do they think about much bigger and much slower unarmored rotorcraft flying over an enemy armed with modern air defense weaponry? Flying dozens of transport rotorcraft over enemy territory, slowing to land troops or airdrop them, then returning with supplies is insane because most aircraft will be shot down on their first mission!

Seabasing Madness

Seabasing became a hot topic this past decade. It is portrayed as a revolutionary idea that allows a light logistical "footprint" by employing just-in-time logistical support. The idea is that an amphibious or expeditionary force need not establish stockpiles of supplies ashore if it can draw whatever it needs from well-organized ships offshore. This is an attractive idea because it eliminates the need to establish stockpiles and fuel farms ashore, facilities for their workers, and security for all.

This seems brilliant, so why didn't the experts of previous wars discover seabasing? First, sealift is finite and armies usually have many times more tonnage to move than sealift. Therefore, they "stage" material near an objective area, then use their limited sealift to shuttle these resources after a surprise landing. If ships linger offshore to provide seabased support, they are unavailable to shuttle supplies from staging areas. Second, a seaborne landing quickly attracts the attention of enemy commanders who vector their ships, attack boats, missiles, submarines, commandos, and attack aircraft toward that area. It is much safer for a ship to offload cargo and depart rather than loiter offshore like a duck in a shooting gallery. Moreover, supplies ashore cannot be sunk by a single torpedo or missile. Since many ships are filled with explosive fuel and ammo, ships may flee at the first sign of an enemy threat.

Third, while rapidly moving supplies from ships to shore on demand seems simple, the "fog of war" will intervene. Bad weather or over-the-horizon communications may leave troops stranded ashore without food and ammo. Helicopters, tiltrotors, and landing craft break down or get shot down while naval forces are often distracted by other priorities. Even an unsophisticated enemy can fire a modern homing torpedo from a fishing boat and sink a ship, causing a Navy commander to order all ships to leave an area. During World War II, warships from the Japanese Navy approached Guadalcanal where US Marines had landed several days before. The US Navy decided to run than fight, taking along cargo ships that were unloading supplies for Marines ashore. The Marines survived on the supplies that had been offloaded, and would call seabasing an impractical and dangerous logistical concept for major operations.

Fourth,

helicopters

and tiltortors cannot

operate safely over areas occupied by a modern enemy and LCACs and Amphibious Assault Vehicles

(AAVs) with thin armor are easy targets should they attempt to land forces along an enemy

shoreline without direct fire support. The biggest

advocates for this flawed doctrine are military contractors eager to sell

ultra-expensive transports. In the December 2001 issue of Naval Proceedings,

Marine Corps Major Chris Wagner from the Strategy Center at Headquarters Marine

Corps revealed: "The OMFTS concept was

developed to create tactical synergy through integration of forces afloat and

ashore, and it was instrumental in justifying major acquisition programs such as

the advanced amphibious assault vehicle and the MV-22 Osprey."

Fourth,

helicopters

and tiltortors cannot

operate safely over areas occupied by a modern enemy and LCACs and Amphibious Assault Vehicles

(AAVs) with thin armor are easy targets should they attempt to land forces along an enemy

shoreline without direct fire support. The biggest

advocates for this flawed doctrine are military contractors eager to sell

ultra-expensive transports. In the December 2001 issue of Naval Proceedings,

Marine Corps Major Chris Wagner from the Strategy Center at Headquarters Marine

Corps revealed: "The OMFTS concept was

developed to create tactical synergy through integration of forces afloat and

ashore, and it was instrumental in justifying major acquisition programs such as

the advanced amphibious assault vehicle and the MV-22 Osprey."

Amphibs Became Huge

These impractical ideas resulted in procurement of dysfunctional "amphibious" ships that are poorly designed. Since there have been no serious amphibious invasions since 1950, doctrine and amphibious ship designs became absurd. The first problem is that amphibs grew into huge ships with massive well and hangar decks. (An LHA interior "hangar deck" is pictured above.) These are filled with ultra-expensive connectors like V-22s that require crews, maintainers, special support equipment, and stocks of spare parts, yet they provide no combat power!

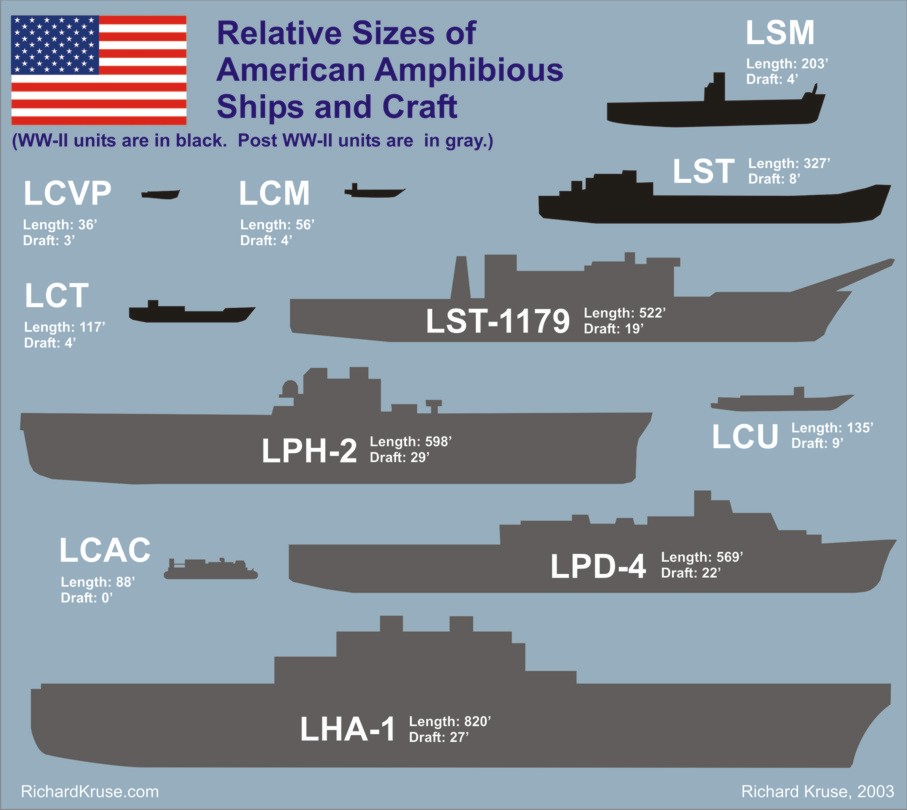

This 2003 graphic shows amphib ship growth since World War II, and they are getting even bigger. This graphic does not show the new America class LHA at 844 feet in length while the new San Antonio class LPD is 684 feet in length. These LHAs are nearly as long as the common US Navy Essex class aircraft carriers of World War II and 25% bigger in total displacement! These dwarf the small, inexpensive, and practical amphibious ships proven during World War II and Korea.

Big ships have deep drafts, so can't go near shore in most areas of the world even if the enemy anti-ship threat is nil. Compare modern amphib monsters with drafts of over 24 feet to World War II LSTs with a draft of just 8 feet. These small ships delivered combat power directly from naval bases and staging areas to the beach without connectors. Unfortunately, odd ideas like well decks and helicopter hangars have warped thinking.

An excellent example is the new San Antonio class LPD (cutaway below). The last in this class is under construction at a cost of over $2 billion, and building will continue as this huge LPD design will replace the much smaller LSDs too, called the LX(R) class. This 25,000 ton ship devotes half its potential cargo space for ultra-expensive connectors that provide no combat power! As a result, it only has room for 800 Marines and 30,344 square feet of cargo. It is vulnerable to attack from shore threats due to its massive size and carries up to 318,308 gallons of JP-5, an explosive aviation fuel that easily ignites.

There are serious proposals to add two 8-cell Mk 41 VLS in the bow of this ship. This would add more costs, more crew, use cargo space, and place 16 large, explosive missiles inside the hull! In addition, LockMart has proposed installing the big Aegis radar system on LPDs, adding much more cost and complexity. These would make this LPD a huge surface combatant, which they should designate as a Landing Ship Destroyer (LPD) to erase the myth that this is an amphibious ship.

Amphibs Became Cruise Ships

Another reason modern amphibs have little room for cargo is the long-term trend in the US Navy to design warships with luxury crew comforts, even for landing force passengers. Ships are designed for peacetime missions that require 6-8 month "cruises" around a world to rapidly execute humanitarian and peacekeeping missions. As a result, they have little space for their traditional role of transporting ground forces to shore. The pictures below are not from Navy bases ashore, but from US Navy amphibs afloat!

These huge amphibs have a weight room, a library, a barbershop, a store with clerks, and some have a museum!

The basic requirement for an amphibious ship is to pick up troops and material from a naval facility or staging area and sail a week to deposit combat power ashore, and then return for another load. Unfortunately, US Navy "amphibs" have devolved into luxury cruise ships with little room for a landing force. If World War II soldiers and Marines (below) saw today's "amphibious" ships, they would be shocked. These guys often "hot bunked" by sharing a bed with sleep shifts. Space was scarce as the ship was designed to maximize cargo and troop capacity. They would be stunned to see exercise bikes and other unneeded luxuries common on today's amphibs.

Amphibs Must Go Back to the Future

The degradation of amphibious lift can be seen by comparing current ships to those used for amphibious landings during World War II. Modern amphibs are much larger yet have far less space for a landing force since most of the ship is devoted to connectors and crew comforts. World War II ships had connectors too, but these were smaller landing craft hoisted topside. They were also heavily armed to engage aircraft and shore threats.

| Amphib class | Displacement (loaded) tons | Navy crew | Troops | Cargo space | Armament |

| Middleton APA 1942 | 16,725 | 538 | 1446 | 200,000 sq.ft | 1 × 127mm gun; 4×76mm guns, 8×40mm guns, 10×20mm guns |

| Haskell APA 1944 | 14,837 | 536 | 1561 | 150,000 sq.ft | 1×127mm gun, 4×twin 40mm guns, 10×20mm guns |

| San Antonio LPD 2006 | 25,000 | 363 | 800 | 30,344 sq.ft | 2×30 mm guns; 2×RAM air defense launchers |

| America LHA 2014 | 45,693 | 1059 | 1871 | 24,250 sq.ft | 2×RAM + 2×air defense launchers; 2×20mm gatling guns; 7×twin 12.7mm machine guns |

Experts are correct when they say the US Navy lacks amphibious lift, but not because of a lack of funding. The problem is that ships procured can't lift much and require fragile connectors that cost as much as the ship itself! Moreover, today's amphibious fleet is not designed to conduct amphibious invasions of a defended coast! This problem is evident in this 2016 article in USNI News about the Navy's newest amphib:

"Several officers emphasized the need to lighten the ground combat element attached to the America ARG. Capt. Homer Denius, commodore of the Amphibious Squadron 3 that will lead the America ARG on deployment next year, made clear that 'that idea of a lighter MEU is going to have to come into concept' ahead of the deployment. The balance is that a lighter maneuver element means America can support a larger maneuver element – and striking that balance was part of the success during RIMPAC. When ground troops moved ashore, the largest vehicle they brought with them was Australian LAVs. Baze said America pushed out a company of Marines on a couple CH-53Es from 50 miles offshore 'before lunchtime,' with the simplicity of moving a lighter company showcasing what America was built to do."

Less combat power ashore is not more. No competent commander will fly 150 Marine infantrymen in several sorties on slow, huge, helicopters or tiltrotors and dump them off in enemy territory 50 miles from ships with no naval gunfire support! What could these stranded riflemen accomplish against a serious enemy force, assuming they survive the landing? It is clear that landing Marines is an annoyance, and this navy commodore was happy to "push out" the Marines "attached to the ARG" in time to enjoy lunch and resume his sea patrol.

The US Navy needs a hundred small, simple, armed, oceangoing amphibious ships (without connectors or aviation fuel) designed to deposit combat power ashore in the face of hostile fire, like World War II era LSTs pictured below. These ships were big and solid enough to withstand shore fire and make it to the beach, unlike LCACs and AAVs, yet small enough to make targeting by anti-ship missiles and submarines difficult. A hundred LSTs are affordable if the Navy cancels plans to replace its twelve aging LSDs with much larger, dysfunctional, and expensive LX(R)s, which are really San Antonio class LPDs. Here is a detailed article on this solution: Landing Ship Assault

Carlton Meyer editorG2mil@Gmail.com

©2017 www.G2mil.com

| Personal Story

I was involved in a MEU planning exercise that involved the common US Embassy rescue scenario. A warlord and his men had surrounded the embassy and demanded surrender. The dozen Marines guarding the embassy would be quickly overrun if attacked. The embassy helicopter pad was only large enough for one aircraft to land and warlord machine gunners surrounded its walls. The only big LZ was a mile from the embassy and landed Marines would have to advance on foot through an urban area and might become pinned down as the embassy was overrun. Officers debated an aerial assault plan for an hour until I disrupted things by making a suggestion. The embassy was just two blocks from a large undefended beach. LCUs with tanks, troops, and trucks could sail at night, quietly hit the beach at dawn, and rush ashore to the embassy in minutes, surprising the warlord soldiers who would flee, with no chance that a helicopter might be shot down. Embassy personnel could be safely evacuated to ships using the bullet proof LCUs. After some comments, the Navy officer in charge announced that Captain Meyer's simple idea is much better than the loud, dangerous, aerial assault that most Marine officers assumed was the only option. |