Readers must familiarize themselves with these subtopics to understand the concepts discussed in this chapter. These articles are linked within this chapter, but it may be easier to read them in advance.

For All Seasons - the old but effective RPG-7

Thoughts on Seabasing - keep troops on ship

Liberty Ships - allow troops to relax away from the locals

OV-6C Rangers - watching insurgents from above

RAH-60 Gunhawks - use the AC-130 concept to fire guns from above

Battalion Scout Helicopters - an inexpensive idea to boost combat power

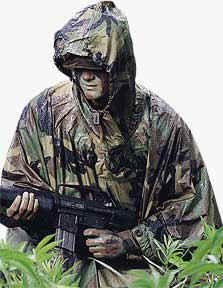

Combat Ponchos - are needed to mask infrared signatures

__________________________________________________________

General William Westmoreland's insurgent tactics during the Vietnam war were simple; take the war to the enemy and kill him faster than he could be replaced. Where possible, apply an overwhelming, stunning force. "A great country", he liked to say quoting the Duke of Wellington, "cannot wage a little war." Westmoreland proudly bragged that his forces were killing ten enemy soldiers for every American that died, so it was just matter of time before they were destroyed.

By 1968, it was becoming apparent that something was wrong with Westmoreland's strategy. The man who sounded the alarm was a lowly Army Lt. Colonel, John Paul Vann, whose life was depicted in an excellent book, "A Bright Shining Lie." Vann had years of experience in Vietnam and explained to anyone who would listen that North Vietnam had a population of 20 million people. Half were men, and half of those were boys and old men, so that left five million fighting age North Vietnamese men. At that time, some 25,000 Americans had died in the war. Vann pointed out that a 10 to 1 killing ratio will cost 500,000 more American deaths to finish off those five million Vietnamese men. This figure didn't even include a million local Viet Cong guerillas in the South, plus Chinese and women volunteers.

Vann showed that at the current rate of killing 100,000 Vietnamese insurgents a year, it would take 50 years and 500,000 American dead to kill those 5 million fighters. However, some 150,000 boys were becoming men each year, so Westmoreland was making no progress at all with his 10:1 kill ratio. Westmoreland eventually realized that his strategy was not working, so he asked for 200,000 more troops to increase the kill rate. There were already 500,000 US troops in Vietnam to crush rag tag insurgents from a small backward nation, so President Johnson told him no. The US military failed in Vietnam, but didn't learn much as an institution as blame was shifted to the media and protesters for ending the war too soon.

During the Vietnam conflict, civilian leaders pressured the US Army to establish

groups of counterinsurgency experts, known as "Special Forces" a.k.a. "Green Berets." The US Army now has five active duty and two

reserve Special Forces brigade-size "Groups" designed to operate in

squad-size components with native forces. Tom Clancy's book "Special

Forces" provides a good overview. These squads are designed to serve

as advisors, they are not commandos, although they often fight with native

forces. Success has been poor because the USA never develops a professional

officer corps.

During the Vietnam conflict, civilian leaders pressured the US Army to establish

groups of counterinsurgency experts, known as "Special Forces" a.k.a. "Green Berets." The US Army now has five active duty and two

reserve Special Forces brigade-size "Groups" designed to operate in

squad-size components with native forces. Tom Clancy's book "Special

Forces" provides a good overview. These squads are designed to serve

as advisors, they are not commandos, although they often fight with native

forces. Success has been poor because the USA never develops a professional

officer corps.

As a result, the regular Army has returned to fight insurgents, along with its traditional method of crushing insurgents with heavy firepower and thus infuriating the local populace and making the problem worse. Bill Lind calculated that killing one insurgent creates two more. Keep in mind that a couple of innocent civilians are accidentally killed for each insurgent, and property damage is sometimes immense. This all creates insurgents, especially in countries where blood feuds are common. Some bewildered US soldiers were confused as to why the Iraqis did not express gratitude for American reconstruction efforts, oblivious that the US military caused all the destruction and chaos in the first place. If someone blew up your house killing your daughter, would you express gratitude if he rebuilt it while you lived in a tent?

Fighting insurgents has become much more difficult since World War II because of two new types of small, simple, and cheap infantry weapons: the automatic rifle (like the AK-47) and the Rocket Propelled Grenade (RPG). (below) This allows small bands of untrained insurgents to unleash bursts of heavy firepower to inflict casualties on well-trained and well-equipped professional soldiers. The creative use of mines and roadside bombs have also become deadly problems as designs can be found on the Internet.

A May 19, 2002

Washington Post article; "Fleeting, long-distance encounters become the norm" provided these interesting quotes. "It's

a frustrating war, "Lt. Col. Patrick Fetterman, the commander of Operation

Iron Mountain, said at the beginning of the mission last weekend:

"The

reason it's so frustrating and aggravating is because the enemy is not fighting.

We're trying to find him and he's trying to avoid us. So any time we go out he

fades away. It's just like Vietnam. Any time he finds a weak spot, he

flows in like water."

A May 19, 2002

Washington Post article; "Fleeting, long-distance encounters become the norm" provided these interesting quotes. "It's

a frustrating war, "Lt. Col. Patrick Fetterman, the commander of Operation

Iron Mountain, said at the beginning of the mission last weekend:

"The

reason it's so frustrating and aggravating is because the enemy is not fighting.

We're trying to find him and he's trying to avoid us. So any time we go out he

fades away. It's just like Vietnam. Any time he finds a weak spot, he

flows in like water."

Apparently, all the lessons learned from Vietnam and all other counterinsurgency campaigns have been ignored. Cautious officers become fearful to employ small teams needed to hunt down insurgents, and those with traditional military training prefer battalion and brigade-size operations with names like "Iron Mountain" to sweep though areas on what they call "peacekeeping operations." However, when they encounter resistance, rather than acting like peacekeepers, they often employ air strikes and artillery causing massive damage and civilian casualties. The Army used large "hammer and anvil" and "search and destroy" tactics in Afghanistan and Iraq. These involved hundreds of soldiers on foot trudging through the "bush" or columns of armored vehicles racing along in hopes they will stumble across a sleeping enemy. This "parade" tactic is simple and safe, but ineffective.

Recruit and Train Local Scouts

Using career counterinsurgency experts is the best option. If these are unavailable, the first step for regular soldiers is to recruit and train locals as scouts. American Indian scouts helped regular US Army units pursue and attack rival Indian tribes in the 1800s. Their expertise of local terrain, languages, and tribal habits proved essential for success. Most Army officers even followed their tactical advice. A notable exception was the dashing Army officer George Armstrong Custer, who disregarded the pleas of his Arikaras and Crow scouts to turn back, leading to the slaughter at Little Big Horn. Local scouts were also used the Philippine campaign and during the Vietnam war.

English language

training is the key focus for training scouts, but they must also learn military terminology, the

use of basic infantry weapons, and become physically fit. They

must be taught about why the foreign troops have appeared and what they want to

accomplish so they can serve as ambassadors to local villages. Scouts should be paid

well as they have no retirement plan and perhaps collect a bonus for each insurgent they help locate. They

enlist for a four-year

term, or until they are no longer needed. At that point, they will receive

a large bonus, which is important to discourage them from deserting with loot or selling

out their foreign employer.

English language

training is the key focus for training scouts, but they must also learn military terminology, the

use of basic infantry weapons, and become physically fit. They

must be taught about why the foreign troops have appeared and what they want to

accomplish so they can serve as ambassadors to local villages. Scouts should be paid

well as they have no retirement plan and perhaps collect a bonus for each insurgent they help locate. They

enlist for a four-year

term, or until they are no longer needed. At that point, they will receive

a large bonus, which is important to discourage them from deserting with loot or selling

out their foreign employer.

The key to successful counterinsurgency is patience. Political leaders must be told that it may take up to ten years. On the other hand, Generals must understand that a nation has limited resources, so they must deploy a minimal force. The presence of foreign troops annoys citizens so military bases should be located in remote areas far from population centers and not alongside a major road. Islands are good, and seabasing is best. Hiring locals to work on bases is usually a bad idea as many become spies and all become envious that foreign troops live in what they consider luxury, while locals are homeless. Therefore, it is better to bring in cheap contract labor from other nations to run base camps.

In many cases, unit rotation is the best method for keeping a small footprint. For example, a rifle company may be needed to support local police in a small city. However, building a camp for them to live in with hot food, showers, entertainment, air conditioning, Internet access, beds and other niceties is expensive and requires a hundred people to support, who in turn need support. Therefore, it may be best to rotate duty between two companies. One stays at a comfortable airbase a few hours flight away for two weeks, while the other deploys and roughs it out on duty in town and eats rations. Two C-130 sorties can rotate these companies every two weeks.

This may seem expensive, yet it is cheaper to deploy a rifle company every two weeks than maintaining a comfortable camp in an insurgent infested area for a rifle company plus the two hundred camp support personnel occupying a large area needed for all of its goodies, which needs two C-130 flights every two weeks for logistical support anyway. Moreover, a deployed rifle company is mobile so it can move where it is needed or every few days to confuse insurgents, whereas a fixed camp must always be guarded and becomes a target for mortars and car bombs.

House-to-house searches for no cause are unjustified and just plain stupid as they infuriate the locals. Firepower restrictions are critical and vary depending on the threat. Infantrymen become angry when their buddies are killed or hurt and will not hesitate to inflict suffering on the local people in the form of air or artillery strikes to retaliate. Locals understand that foreign troops can fire back if someone fires at them. They do not understand if two houses blow up from air strikes killing several civilians because the foreigners said they thought insurgents might be there or because someone fired a few sniper rounds.

Deployed troops need entertainment on their base or a vacation elsewhere every few weeks to relax. Liberty Ships are ideal. It is usually not a good idea to allow them to seek entertainment locally as that raises security problems and causes conflicts with locals. Combat pay equal to double base pay is desirable for good morale.

These are general rules as every insurgency is different. After the 2003 US invasion of Iraq, a small insurgency grew rapidly as the US Army ignored these basic counterinsurgency rules. In future conflicts, these issues must be addressed and a plan developed. In addition, certain aircraft are needed for effective counterinsurgency operations, like OV-6C Rangers, RAH-60 Gunhawks, and Battalion Scout Helicopters. Once large numbers of local scouts have been trained and assimilated into units, counterinsurgency operations can begin. There are four types of effective counterinsurgency strategies that can be employed:

Train a National Army

Most Americans fail to understand that military service in most countries is considered an opportunity to become rich and powerful. It takes years, if not decades, to train an honest officer corps. The combat training is the easy part, the challenge is teaching new officers not to steal, not to set up money making rackets, not to abuse civilians, not to ignore laws, and not overthrow the civilian government. They may have no confidence in promises for a pension after 30 years or lifetime medical care if injured in service. As a result, they prefer to stay at their base and have a good time rather than leading patrols into the dangerous boondocks looking for trouble.

A sharp looking, tactically trained army can be

formed within a year at considerable cost. However, the habits of a culture remain, so as soon they are allowed to operate

independently the

officers set up businesses to make money and enjoy the good

life. This is why "advisors" must personally control payroll,

and constantly check messing and supply to discourage theft. Another

problem with forming new national armies is that pay is the primary motivation.

Even when pushed to fight insurgents, they avoid serious combat with

parade tactics and

often enrage the local populace with arrogant behavior. This was a problem faced by the US Army in Vietnam,

Iraq and Afghanistan.

A sharp looking, tactically trained army can be

formed within a year at considerable cost. However, the habits of a culture remain, so as soon they are allowed to operate

independently the

officers set up businesses to make money and enjoy the good

life. This is why "advisors" must personally control payroll,

and constantly check messing and supply to discourage theft. Another

problem with forming new national armies is that pay is the primary motivation.

Even when pushed to fight insurgents, they avoid serious combat with

parade tactics and

often enrage the local populace with arrogant behavior. This was a problem faced by the US Army in Vietnam,

Iraq and Afghanistan.

Train Local Villagers

It's much faster and cheaper to arm local villagers to defend themselves and to train a small cadre of scouts than attempt to form a national army. US Special Forces "Green Berets" train and pay local villagers to hunt and destroy the enemy in their area, which is the strategy they used in Afghanistan. This saves American lives and is often successful if the insurgents are not of the same ethnic group. For example, the German SS formed Albanian units during World War II to fight Serbian insurgents. Green Beret led Montagnard tribesmen who live in the remote mountains of Vietnam fought successfully against the Vietnamese insurgents who came from the lowlands. The book "Inside the Green Berets" provides an excellent account.

However, this strategy does not work when the locals are supportive of the insurgents. In many parts of Vietnam, the foreign Green Berets had trouble motivating local villagers to go out and kill their friends and relatives hiding in the jungle from the invading Americans. The villagers played along to collect free food and weapons, but were unenthusiastic and the weapons and ammunition provided by Americans were often forwarded to the insurgents themselves. The Japanese had the same trouble in 1944 when they formed Filipino units to help them fight Filipino insurgents.

Even when successful, this strategy causes other problems. Well-trained and equipped local forces are likely to fight against any outsiders, including the official central government. This has become a problem in Afghanistan where the US Army trained a national Afghan Army to rule the country. However, the Green Berets trained local villagers to fight outsiders. Young men from impoverished nations quickly learn to enjoy the life of "soldiering." If a foreigner announces victory and asks for their weapons, militiamen become angry and refuse, and the foreigner will not press the issue. So when the conflict is over, thousands of well-trained, well-armed mercenaries have no jobs or have become too lazy to work on farms, so a new conflict begins. The most recent example is Iraq in 2014, where local Sunni militias armed by the US Army turned against the central government in Baghdad.

Employ Small Teams

Problems with using local forces prompted the British to use small teams to

fight an insurgency in Malaysia in the 1950s. Small teams of four

men can move quietly around the countryside observing activity. They can

call-in air or artillery strikes against groups of insurgents and locate

insurgent base

camps that can be attacked by larger forces. They may conduct ambushes or

use sniper rifles to kill small groups of insurgents. As infrared imagers

become inexpensive and sold over the Internet, insurgents are likely to obtain

them. Therefore, teams need a new type of combat

poncho that shields most of their body heat. Snipers say that charcoal-lined

NBC suits work well, but Mylar lining should work better.

that shields most of their body heat. Snipers say that charcoal-lined

NBC suits work well, but Mylar lining should work better.

Such "direct action" is risky because gunfire quickly attracts other insurgents and the small team hasn't the firepower to fight them. The United States used small teams successfully in Vietnam, called Long Range Reconnaissance Patrols (LRRP)s by the Army, and "Recon" by the Marines. The outstanding movie "84 Charlie Mopic" shows this tactic. The drawback to small teams is sometimes they never return, which is why most soldiers in Vietnam disliked this concept. However, these small teams felt safer moving swiftly and silently by themselves rather than joining in a company parade through the jungle with heavy weapons until the enemy chose to ambush them. The beginning of the movie "Platoon" shows the parade tactic.

Checkerboard Squads

A new tactic was developed by US Army Colonel David Hackworth after watching the Army fail for two years in Vietnam, which he describes in his outstanding book "About Face." American GIs rarely found Viet Cong camps and the enemy were experts at hit and run ambushes. The average soldier didn't have the fitness, training, or motivation to operate in small teams for long-range patrols. Therefore, Hackworth attached a machine gun to each squad and deployed these 14-man squads about 1000 meters apart in a huge checkerboard formation. The soldiers were not enthusiastic about the idea at first because they feared encountering a large enemy formation. However, Hackworth knew that insurgents only massed in large units for a carefully planned attack, and never made impromptu "Banzai" charge; they ambushed and ran. In the worst case, the squad had plenty of firepower to hold off a large unit for five minutes until several squads arrived to reinforce.

These squads moved much quieter and covered large areas as they coordinated movement by radio. In cases of confusion, every squad marched to the sound of guns. A hidden enemy was much more likely to open fire on a squad not knowing other squads were nearby. If a lead squad made contact, the squads on each flank would move forward to envelop while the rearward squads advanced to support. Sometimes the middle squads made contact and the forward squads moved to encircle. The tactic was very successful and Hackworth eagerly shared his discovery only to find little interest among officers rotating through for their six months of command time. Coordination seemed tricky, no one had heard of such a tactic, and career officers did not want to take risks with new ideas. Company and battalion parades though the countryside was easier, safer, and allowed officers to orchestrate the action directly without relying on NCOs.

Parades in Afghanistan

Over 40 years later, most US Army officers still prefer parades over proven counterinsurgency tactics. The Washington Post article quotes Lt. Col. Fetterman: "We had no movement in here last night. That means their 'intell' is better than ours. They know where we are and we didn't know where they are." It's not surprising the Taliban noticed Fetterman's 129 soldiers parading through the countryside and managed to scamper out of their path. While discussing the operation, Fetterman's sergeant major made a comment that revealed a hot issue: "But until we're ready to accept putting out squads." Fetterman interjected "We're not willing to do that." The sergeant major replied "I know that."

Obviously, an officer in the chain-of-command decided not to employ effective tactics because it entails greater risk. It's possible that a small team could be trapped and killed by the Taliban, so its best to just conduct parades through the countryside. Officers can secure credit for a combat tour in Afghanistan without suffering a single casualty in their unit. Small teams may prove effective in Afghanistan, but American soldiers may die. While a missing recon team in Vietnam was not worthy of mention at the daily press conference, a missing team in Afghanistan may prompt an investigation and probably a poor performance eval.

After two years of parades, US Army has began to use the checkerboard squad tactic, or at least "checkerboard platoons" as described in this article: Small units lure Taliban into losing battles where an Army Lieutenant said: "We've had a lot of success with textbook tactics, getting the smallest element engaged, and then using other assets to just pile on," says O'Neal. "The Taliban are more willing to engage with us when we have smaller numbers."

This 2009 picture shows how not to fight insurgents.

Marine Generals had great fun with an offensive in southern Afghanistan as 4000

Marines road marched in hot weather for miles and found almost nothing. While

grunts labored with huge loads marching in the hot sun, Generals watched computer screens at air

conditioned command centers showing the "attack" and helicoptered

around the "battlefield." Lots of press, lots of talk, but no results except for

wasted money and demoralized Marines. An outstanding documentary describes why

the USA failed in Afghanistan: This

Is What Winning Looks Like.

This 2009 picture shows how not to fight insurgents.

Marine Generals had great fun with an offensive in southern Afghanistan as 4000

Marines road marched in hot weather for miles and found almost nothing. While

grunts labored with huge loads marching in the hot sun, Generals watched computer screens at air

conditioned command centers showing the "attack" and helicoptered

around the "battlefield." Lots of press, lots of talk, but no results except for

wasted money and demoralized Marines. An outstanding documentary describes why

the USA failed in Afghanistan: This

Is What Winning Looks Like.

Small Wars

The US Marine Corps has historical experience with counterinsurgencies, which it prefers to call "small wars." It maintains an outstanding website with a host of information: US Marines Small Wars, which includes a recommended reading list. Books provide examples of innovative tactics. For example, a fascinating book is "The Devil's Guard" about ex-Nazis fighting for the French Foreign Legion in Vietnam in the early 1950s. The Viet Cong guerillas hid among the villagers and were very difficult to identify since they always had local security to warn of approaching French forces. One tactic the French Nazis developed was for two sharpshooters from the back of a patrol to stealthily drop into the bush as they entered a village. The column would pass through as the villagers waved or ignored them.

After the column faded into the distance, the two sharpshooters watched for interesting activity. Sometimes, a few excited villagers would appear from nowhere to discuss things, often with weapons in hand. Sometimes a villager would set up a radio set, or a farmer would retrieve a hidden rifle. If the column heard their sharpshooters open fire, they would hurry back to the village to investigate, otherwise they would pause to allow the sharpshooters to catch up after dashing around the edge of the village.

Counterinsurgencies require different training, organization, and equipment than those needed for large wars. Soldiers must act more like a police SWAT teams than an armored task force. Armies of smaller nations need to study this topic as well since they are likely to participate in UN peacekeeping missions. In fact, it is often better for troops from nearby nations to fight insurgencies since they are far more knowledgeable about the language and culture than some distant Western nation. Counterinsurgency is a game of wits and strategy, it is not won by attrition, firepower, technology, nor large ground operations called "Iron Mountain."

Checkpoint Tactics

Checkpoints are an effective counterinsurgency and counterterrorism tactic. Although it seems simple, there is strategy involved. They should be used at random locations for only around 30 minutes at a time because in an era of cell phones, checkpoint locations are quickly broadcast. In addition, those manning a checkpoint are easy targets, so its best to move frequently. Finally, those manning checkpoints must remain alert and ready for action and that becomes difficult after 30 minutes. Therefore, a typical checkpoint team will throw up a checkpoint for 30 minutes, then move to a safe location to rest for 30 minutes or transport prisoners, then select a new location.

The selection of a checkpoint is key. Everyone assumes that its best to locate around the bend in a road or just over a hill so drivers suddenly encounter the checkpoint, where there are no place for cars to u-turn or turn off on a small connecting road. However, traffic is often so heavy that most cars must be waved through with no inspection. In such cases, it is best to locate the checkpoint so that drivers can see it at a distance, and where places exist to u-turn or turn off on a small connecting road.

Someone hides alongside the road to observe cars as they approach the line of cars slowly moving toward the checkpoint, while another team is located where cars attempting to evade the checkpoint will travel. This often prompts "persons of interest" to reveal themselves as they attempt to avoid the checkpoint. Police departments often use this tactic at drunk driving checkpoints.

©2015 www.G2mil.com