Here is a summary of the four known major V-22 "Class A" mishaps these past two years:

April 8, 2010 - Afghanistan, CV-22 crash, 4 dead, 16 injured

Details on this CV-22 Crash, caused by exaggerated performance data in the flight manual or a minor engine problem. A V-22 tiltrotor is unable to employ autorotation to land safely when engine power is lost or degraded because its rotors are much smaller than a helicopter's.

Here are parts of G2mil articles that warned of this:

Dec 2003 - Why the V-22 is Unsafe - IDA analysis

During peacetime, losing power to just one engine is not uncommon, known as One Engine Inoperative (OEI). If this occurs in a loaded helicopter, most lack the power to stay airborne and begin a controlled descent. Helicopters can land safely at half power if the pilot descends rapidly enough to flare before landing, just like with autorotation. But what happens to a loaded V-22 which loses one engine while its rotors are upright? While the segmented cross-shaft should ensure power to both rotors, its rotors cannot allow the V-22 to flare, so it will hit the ground very hard.

This is a key issue, yet the program has refused to test a one engine out vertical landing of a loaded V-22. They say a V-22 can convert to the airplane mode and land safely at an airfield with a rolling landing with just one engine. However, a V-22 with rotors up may be too close to the ground to allow conversion to the airplane mode as it falls. This also assumes that a friendly airfield is in range, which is rarely the case while operating from ships at sea.

Nov 2008 - Why the V-22 is Still Unsafe - numerous flaws

NATOPS is Hyped

Many pilots are shocked to learn that the charts in the V-22 Naval Air Training and Operating Procedures Standardization (NATOPS) are inaccurate. This is the pilot users manual relied upon for safe operation. The demonstrated performance of V-22 was so poor that Bell-Boeing executives decided to insert old optimistic "projected" performance data into NATOPS' range and payload charts. New V-22 pilots learn from others that NATOPS is hyped, but this still endangers flight crews who must learn the V-22's limitations through experience and guesswork.

_______________________________________

July 7, 2011 - Afghanistan, V-22 in flight, 1 dead

Cargo slid out the back of a V-22 as it took off, taking a Marine crewman with it. Although the Marine Corps mishap report clearly indicates the aircraft was airborne "200 feet" off the ground, Generals chose to label it as a ground mishap, so it is not counted against the V-22 safety record. I guess they can claim the Marine didn't die while in the aircraft, only when he hit the ground. One could claim that all crashes are "ground" mishaps, since they occur on the ground. However, the Navy Safety Center lists it a Class A FRM (Flight Related Mishap), just like a similar mishap involving a Marine CH-53E in 2005.

Class A Mishap

Naval Safety Center Web Enabled Safety System

Rpt No:AV-201Mishap Date

07/07/2011 Reference HT ID 1320850600993 Time 1015 Severity A FRMCustodian VMM 264

Fatalities 1

MV022B Count Y Destroyed N

Buno 167902

Location SHORE Event occurred at a Marine Corps forward operating base in rural Afghanistan.

Summary Crew chief was ejected out the back of an MV-22B from 200 feet

Event Cost $270,000

The

Marine Corps has failed to report a dozen Class A mishaps, even when a V-22 is

scrapped afterwards. The photo at right is a V-22 after a 2007 inflight fire that

destroyed the $2 million engine and burned up the nacelle, but the mishap was

misreported as a Class B. Some details of unreported mishaps were published

by a Navy observer in 2009 and a follow

up appeared in "Wired" last year. Congress took an interest in 2009, and after much

stonewalling, the Marine Corps admitted

that 29 of its 105 new V-22s were not flyable. Half of those can be traced to

retired test aircraft and crashes, but the Generals did not provide details on

why more than a dozen of their new V-22s had become permanently "unflyable".

The

Marine Corps has failed to report a dozen Class A mishaps, even when a V-22 is

scrapped afterwards. The photo at right is a V-22 after a 2007 inflight fire that

destroyed the $2 million engine and burned up the nacelle, but the mishap was

misreported as a Class B. Some details of unreported mishaps were published

by a Navy observer in 2009 and a follow

up appeared in "Wired" last year. Congress took an interest in 2009, and after much

stonewalling, the Marine Corps admitted

that 29 of its 105 new V-22s were not flyable. Half of those can be traced to

retired test aircraft and crashes, but the Generals did not provide details on

why more than a dozen of their new V-22s had become permanently "unflyable".

______________________________________________________________

April 11, 2012 - Morocco, V-22 crashed, 2 dead, 2 injured

Marine pilots lost control in high winds during the V-22's unique PUWSS phase, which occurs when the downwash from the tilting rotors hits the aircraft's tail (empanage). The investigation is ongoing and no pubic announcement has been made, but an internal memo noted:

"After it finished turning, it had tailwind. The pilot tilted the nacelles forward. The moment arose around the vertical with flying low speed because of the travel of the center of gravity forward due to the movement of nacelles and tailwind."

Mishap Date

04/11/2012 Reference HT ID 1334166529105 Time 1555 Severity A FMCustodian VMM-261

Fatalities 2

MV022B Count Y Destroyed Y

Buno

165844Location ATLANTIC OCEAN (EASTERN - EASTLANT) MOROCCO SHORE NW of Paige Blanche Int'l airport

Summary MV-22B crashed during day VFR departure from LZ in Morocco. 2 fatal, 2 injured.

Event Cost

$68,091,663Previous G2mil articles described the difficulties in flying a V-22 in windy conditions:

Dec 2003 - Why the V-22 is Unsafe - IDA analysis

In addition to the problems described above there are other V-22 idiosyncrasies to confront the careless or fatigued pilot, pitch-up with sideslip and over-modulation of nacelles being two of the most significant.

Nov 2008 - Why the V-22 is Still Unsafe - numerous flaws

Pitch-Up With Side-Slip (PUWSS) is a problem unique to the V-22. As the rotors tilt upward to the hover mode or transition to the airplane mode, the V-22's strong downwash suddenly blasts its tail empanage, causing the nose to rise sharply and the aircraft to slip toward one side. Test pilots found this disturbing, so flight control software automatically dips the nose when this occurs. This works well in still-air, but high winds or maneuvering during the PUWSS computer auto-correction phase is dangerous.

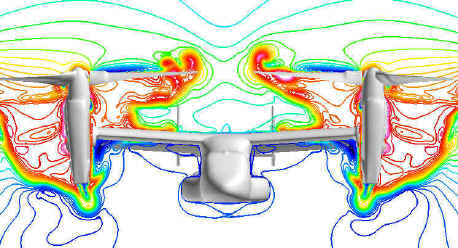

A

third problem is the V-22's boxy fuselage, which provides more internal volume

than older cylindrical shapes, although 25% less than the CH-46E. However, this

allows high winds to push it sideways, a situation made worse by the large side

profile of the engines and tail. This makes hover operations in high winds

dangerous as the V-22 wants to "weathervane" and turn. A V-22 requires

up to 80% more power to hover in high winds, and if extra power is not available

because it is loaded with payload, control may be lost. A 2005 NASA

study (pdf) provides details on this problem.

A

third problem is the V-22's boxy fuselage, which provides more internal volume

than older cylindrical shapes, although 25% less than the CH-46E. However, this

allows high winds to push it sideways, a situation made worse by the large side

profile of the engines and tail. This makes hover operations in high winds

dangerous as the V-22 wants to "weathervane" and turn. A V-22 requires

up to 80% more power to hover in high winds, and if extra power is not available

because it is loaded with payload, control may be lost. A 2005 NASA

study (pdf) provides details on this problem.

The Marine Corps has avoided this problem by imposing flight limits in bad weather. However, this mishap occurred during a major exercise with many VIPs in attendance. It would be very embarrassing to keep the V-22s grounded because of winds while helicopters flew. One can blame the pilots, stating they must not transition from a hover to the airplane mode in strong winds. However, landing and taking off from an LZ requires much concentration, and its difficult for pilots to note wind speed and direction as they depart. The flight software became confused as well, causing an "over modulation" i.e. over correction. It's difficult to blame the pilots, except for attempting to fly in windy conditions. On the other hand, weather conditions may change rapidly, and may not be known hundreds of miles from their base.

_______________________________________________________________________________

June 13, 2012 - Florida, CV-22 crashed, five injured

A CV-22 got to close to another, knocking some air from under one proporotor and causing an instant snap roll. As reported by the wing commander.

“It was a two aircraft formation training. When the lead aircraft turned around they could not see their wingman behind them. They did a brief search and found the Osprey had crashed on the range,” said Col. Jim Slife, commander for the 1st Special Operations Wing. Officials said the Osprey was found upside down, on fire."

The flight restrictions below are from the current V-22 NATOPS (pilot's manual):

VTOL/CONV: Minimum separation is

250 ft cockpit-to-cockpit and 25 ft of step up. During approach and landing

phase, maintain step up until lead lands or maintain 250 ft separation. While

maintaining 250 ft separation, avoid 5 to 7 o'clock position downwind of the

upwind aircraft.

a. Crossovers in descending, turning flight prohibited.

b. Crossovers in descending, wings level flight prohibited with ROD in excess of

500 fpm.

c. Crossovers shall maintain at least 50 ft of step-up.

___________________

These V-22 limits were imposed because the wake or downwash from another aircraft can affect one tiltrotor before the other, causing an instant snap roll and crash. As a result, V-22s must remain a football field apart and fly at different altitudes. A "wave" of V-22s is never more than three aircraft, and only one can take-off or land at a time. Such restrictions do not apply to helicopters. One can blame the pilots, but they maneuver and cannot see everything 360 degrees around them as they perform other tasks.

The Pentagon's V-22 Safety Report addressed this flaw, with G2mil comments in black:

Dec 2003 - Why the V-22 is Unsafe - IDA analysis

5.

SUSCEPTIBILITY TO WAKE AND TIP VORTICES

There is considerable flight evidence to indicate that V-22 response to the interception of a wake or wing-tip vortex by one of the prop-rotors can be an un-commanded roll[6]. There have been at least three cases where an un-commanded roll was experienced in a V-22 as a direct result of flying in proximity to another aircraft. NAVAIR and Bell/Boeing have addressed this problem by placing strict operating limitations on the allowed proximity to other aircraft – currently 250 feet laterally with at least 50 feet vertically. There are two concerns here: First, both wake and wing-tip vortices are known to persist for a very long time and for long distances depending on wind conditions. The FAA guidelines are to remain at least 2,000 feet from other aircraft to avoid intercepting such vortices. Second, in situations of low visibility or confined landing areas, pilots are likely to ignore this limitation to some degree. Flight testing to quantify the degree and extent to which this is a real problem in V-22 (TR-65) is planned but as of now remains to be conducted. Given that air assault, one of the V-22’s primary missions, is by definition many aircraft landing in the same general location at the same time, there is cause for concerns.

Tendency to PIO - Susceptibility to Wake and Tip Vortices

In September 2004, a V-22 pilot attempted to reassure aviators that VRS was no longer an issue with an article in Naval Proceedings magazine. He didn't claim the problem has been solved, but that it is better understood. The V-22 test program had conducted several VRS tests at high altitude. He noted:

"During our testing, we experienced 12 roll-off events, 8 to the right and 4 to the left. The direction of roll off was not predictable from the cockpit. In fact, the cockpit characteristics approaching VRS were not as well defined as in single-rotor helicopters. We noticed a slight increase in vibration, rotor noise, and flight control loosening that would not in every instance foretell of an impending roll off. Each roll off, however, was characterized by a sudden sharp reduction of lift on one of the two proprotors, resulting in an uncommanded roll in that direction. We also noted that roll offs required nearly steady-state conditions to trigger them. Any dynamic maneuvering tended to delay or prevent a roll off from occurring. On many occasions, we entered the VRS boundary during dynamic maneuvers and then exited the boundary without encountering a roll off."

Warning systems have been designed to help pilots stay out of VRS, but pilots may ignore such devices in combat. Although pilots testing VRS easily regained control, they had plenty of altitude and focused exclusively on VRS. However, pilots flying operational missions will have a dozen other things on their mind and may not respond to VRS warnings for several seconds. And there will be no VRS warning from ground effect imbalances, high winds or wake and wing tip vortices from nearby aircraft. As a simple example, if you are driving a test car to see how it handles during a tire blow out while rounding a corner, you will be prepared to handle that emergency and can "prove" it is not a problem. Yet if you are driving in the rain while looking at a map as children play in the backseat and a tire unexpectedly blows out while rounding a corner, you may lose control.

As that V-22 test pilot noted:

"We noticed a slight increase in vibration, rotor noise, and flight control loosening that would not in every instance foretell of an impending roll off. Each roll off, however, was characterized by a sudden sharp reduction of lift on one of the two proprotors, resulting in an uncommanded roll in that direction." Once again, this problem is unique to the V-22, and is mostly likely to occur while pilots are focused on complex tasks related to approaching a landing zone or ship. Moreover, they may not have enough altitude to tilt their rotors forward to regain control should VRS warnings sound. Lastly, transport helicopters often fly in close formation. Suddenly tilting rotors forward to avoid VRS is likely to cause a collision with an aircraft in front, or possibly a building or mountain.__________________________________________________________________

Nov 2008 - Why the V-22 is Still Unsafe - numerous flaws

The fourth problem is that the downwash or the wake from nearby V-22s and helicopters can cause more lift to occur on one rotor than the other, causing a snap roll. Downwash from other aircraft can impinge on one wing, causing it to dip down and bang the engine on deck, even while parked, as described in this internal NAVAIR report (pdf). This is why one never sees V-22s flying in the hover mode in close formation. NATOPS requires a 250ft. separation between V-22s to avoid VRS, which can cause a V-22 to instantly snap roll.

Standard Marine Corps helicopter assault tactics land six CH-46Es in a football field sized LZ, yet only two V-22s can safely land in that size LZ at the same time. Here is a video clip of V-22s attempting an assault landing. They must select a hard surface LZ, lest their heavy downwash clog their engine filters. They must land very slowly to avoid VRS. They can get three in the LZ if one lands first, as this video clip demonstrates. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n1oekSObO3I This also dispels the myth that V-22s can land in an LZ faster than helicopters.

These four issues combined with the inherent instability of the tiltrotor and other issues like VRS, bad weather, unexpected wind gusts, and minor pilot error can overwhelm the flight control computer. This already happens in less complex environments, causing a temporary loss of control. This is no problem unless an aircraft is close the ground, like with the B-2 in Guam. However, a V-22 is likely to encounter such conditions attempting to land or take-off near the ground, and given its high sink rate and tendency to snap roll, its flight control computer may not have a couple of seconds to stabilize the aircraft before it rolls over.

_______________________________________________

Comments posted by a Special Operations pilot at an on-line forum provide insight:

They were flipped over in 'airplane' mode, crashing into the trees (or

onto A-78, the range) and no one was killed? Sounds kind of sketchy to

me, aircraft zipping along and crashing at aerial gunnery speeds don't

result in wounded crewmen who leave the hospital in a few days or a

week. Sounds to me like they were doing gunnery from a hover mode (which

you aren't supposed to do unless over an LZ, which doesn't exist at A78,

at least not for CV-22s), one bird got some dirty air from the other and

a 'roll over' did occur, but in a hover operation that they shouldn't

have been doing. Hence the need to fire Matt Glover (the squadron CC),

they were dicking around and not following correct range procedure and

smashed an aircraft in the process. I almost saw a CV-22 do the exact

same thing at Baker LZ (big patch of grass and sand on the airfield at

Hurbie) trying to do two-ship operations, chalk two got into the dirty

air of chalk one and almost lost control of the aircraft. Thought I was

going to see a Class A right in front of me. I also saw the CV-22 twice

set Baker LZ on fire with their exhaust heat, that bird has some real

design 'issues' (would say problems, but apparently some folks don't

like that word, so I'll stick with 'issues')

Sucks to hear that 'G-Lover' is getting thrown under the bus for this.

But hell, considering that they let the Group Commander, a bird colonel,

almost crash a CV-22 8 months ago when he put one into the trees just

south of Big T LZ and managed, by the Grace of God, to get it back

airborne with only some damage to the nacelles and wing flaps (and

remained in place as the Group Commander, go figure), tells you all you

need to know about how things work in the Air Force these days.

Apparently, this is how it goes these days:

Happen to be a lieutenant colonel in charge of a squadron that has a

crash he had no way of preventing or foreseeing - get fired and have

your name and picture splashed all over the internet with no hope of any

future promotion or position of authority.

Happen to be a full-bird colonel (C-130 pilot, no less) who attempts to

tactically fly and land an aircraft he was totally unqualified in,

almost crashed, flies the damaged tilt-rotor back to base, hops off and

allows the crew to continue flying for two more hours - get downgraded

in your primary aircraft (the Herc) for a week, then get requalified and

stay on as the Group Commander with a possible shot at Brig. General.

Difficult to say why the 8th left OEF. The CV-22s are hard to fit into

most SOF current operations because they really are unique airframes and

require concrete or asphalt landing pads for any kind of sustained

operations. You can't use them for MEDEVAC or CSAR, the downwash is too

massive. The dirt and dust of Afghanistan (and pretty much any other

dry/desert area) eat their engines up at a phenomenal rate. I heard one

rumor that they were replacing those Rolls-Royce engines every 70 to 100

hours, sometimes even less. Those engines cost a mint, so you can

imagine how that affects the cost of a downrange deployment (or even

home station training). Add in the hydraulic problems (5000 psi system

vs. the 1500 to 3000 psi used in all other rotorcraft and C-130s) and

software issues and it's just too complicated of a bird for combat

operations.

Having said all that, I think the concept of the V-22 is legit. We do

need something that breaks us out of this 140 KIAS limit we seem to be

stuck in with helicopters. I'm all for pushing forward with new designs

(Sikorsky has come up with some really cool new versions of the

helicopter recently, for example).

The problem is, the Marine Corps convinced themselves that they needed

to rush it through test and development to replace the incredibly old

CH-46s and the USAF went along with them. So now, you have an

operational aircraft that is still having test phase kinds of teething

issues and people are dying trying to make it work in the operational

side.

In my eyes, they need to transfer all the birds to the USMC, send them

up to Pax River and finish testing and modifying them. The CV-22 is not

ready for prime time, simple as that. Maybe in 5 or 10 years after more

test and development, but right now, it's a widowmaker.

Is the V-22 Unsafe?

A 2003 study funded by the Pentagon concluded:

"The bottom line is that all of the these concerns argue that V-22 is likely to have a larger accident rate when operating within a combat or hostile environment than any conventional helicopter simply because the aircraft has many more ways of getting into trouble than does a conventional helicopter. Unfortunately, all of these issues are the result of basic design features in the V-22 and cannot be changed – the side-by-side rotor configuration, the high disk-loading, and the roll/yaw control implementation through differential thrust. There is not much that can, physically, be done about it. Extensive education and training of aircrews and better warning systems will certainly help, but will not remove the fundamental susceptibility."

What do the aviation experts from around the world think of the tiltrotor concept? No one has purchased any from Bell-Boeing, and no one is designing their own tiltrotor aircraft. The U.S. Army, Navy, and Coast Guard do not want them, nor do any airlines or foreign military services, despite the constant spin that some nation "is expressing interest!" The Special Operations command chose to buy more H-47s and wants no more CV-22s, and the U.S. Air Force has refused to consider them to replace their aging H-60 CSAR helicopters. Meanwhile, Bell helicopter abandoned its civilian tiltrotor program and just introduced a new medium lift helicopter, at one-sixth the price of a V-22.

Recent V-22 Media Spins

V-22 success stories have been spun in the press this past year. Two V-22s flew to pick up a downed Air Force pilot in Libya, something no helicopter could accomplish. They didn't report that two Marine CH-53s flew alongside the V-22s carrying troops in case combat was required. And why were big, old cargo helicopters sent along to carry troops, when the ship had six other V-22s aboard? That rescue was not nearly as difficult as the 1995 rescue of a downed Air Force pilot in Bosina, which was accomplished by two Marine CH-53s.

When our elite SEAL force flew into Pakistan to kill Osama Bin Laden, they chose old H-60 helicopters rather than their new CV-22s. Perhaps the H-60s were chosen because they are smaller, but the larger backup aircraft that were also used for this mission were CH-47s. As our military began its drawdown in Afghanistan, the first aircraft sent home were the new CV-22s! And the Marine Corps delayed the retirement of their 30 remaining 45+ year old CH-53Ds and sent them to Afghanistan, rather than send more new V-22s.

An amazing spin was how the Marine Corps increased its total buy from 360 V-22s to 384, claiming this will save $1.75 billion. Marine aircraft are purchased through the Navy. Three decades ago, the Navy expressed interest in 48 HV-22s for shipboard use, but found them unsuitable due to extreme downwash, and chose the MH-60S for this role over a decade ago. However, the V-22 program kept the Department of the Navy order of 408 V-22s on the books. As the final production run of the V-22 is planned, no one pretends the Navy will get 48 V-22s, so the Marines laid claim to the 48 extras, and announced that it would help "save" money by adding just 24 of the Navy's unwanted 48 V-22s to their order.

This game is working its way through Congress as the Bell-Boeing team works to lock-in another five-year production contract. They hope Congress will not notice the Marines added 24 V-22s to their requirement, and this five-year $8 billion buy increases the cost of each V-22 from $62 million in the current five-year contract, to $81 million for each of 98 more V-22s over the next five years, a 30% increase! The Marines would yield far better results by ending the V-22 program and using those funds to procure needed H-60 Medivac helicopters, as explained here:

The

Marines rely on the Army for medivacs in Afghanistan, as they did in Iraq. The

V-22 program consumed so much of the Marine Corps' "blue" budget for

decades that no thought was given to procuring medical evacuation helicopters,

like the Army's proven UH-60Q, pictured at left evacuating a Marine wounded by

an IED in Afghanistan in March 2010.

The

Marines rely on the Army for medivacs in Afghanistan, as they did in Iraq. The

V-22 program consumed so much of the Marine Corps' "blue" budget for

decades that no thought was given to procuring medical evacuation helicopters,

like the Army's proven UH-60Q, pictured at left evacuating a Marine wounded by

an IED in Afghanistan in March 2010.

Although the V-22 is 30% faster than the H-60, its large size, limited maneuverability, and intense downwash severely limits its LZ options. Moreover, the UH-60Q is customized for medivac, with better lighting, lockers full of medical supplies, a powerful heating system to prevent shock, with oxygen and chest suction systems. A version of the H-60 is in production for the Navy, so purchasing a "navalized" Marine version has been an option for years. As Marine Corps CWO2 Keith Marine stated about operations in Afghanistan: "Luckily the Army and Air Force guys will drop right where you want them to pick up casualties, we are lucky to have them."

Carlton Meyer editorG2mil@Gmail.com

©2012 www.G2mil.com